Words carry history. Some travel across time and culture, changing shape and meaning while keeping a pulse of human experience inside them. One such word is sein. It’s short, elegant, and deceptively simple—but depending on where you stand, it means very different things. In German, it’s the beating heart of every sentence. In French, it’s an intimate, physical term. In philosophy, it’s one of the biggest questions imaginable: What does it mean to be?

This article explores the many faces of sein—how one small word connects language, life, and existence itself.

1. In German: Sein – The Verb That Means to Be

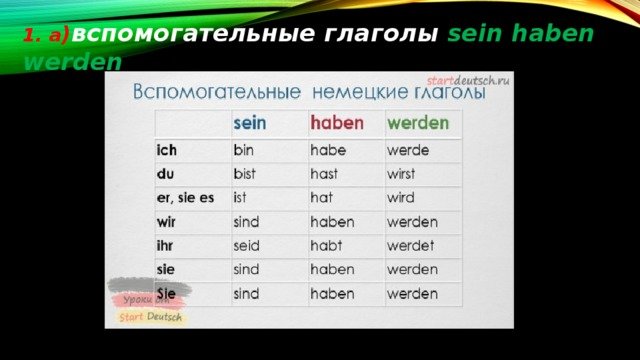

If you’ve ever studied German, sein is probably one of the first words you learned. It’s the infinitive of the verb “to be.” Like its English cousin, it’s irregular, ancient, and absolutely unavoidable.

Here’s how it looks in everyday use:

- Ich bin – I am

- Du bist – You are

- Er/sie/es ist – He/she/it is

- Wir sind – We are

- Ihr seid – You (plural) are

- Sie sind – They are

German learners quickly realize how central sein is. You need it to describe identity (Ich bin Student – I am a student), feelings (Ich bin müde – I’m tired), and even location (Ich bin hier – I’m here).

But sein isn’t just practical. It’s linguistic glue. Without it, conversation falls apart. It shows not only existence, but relationship—between subject and world, between person and state. The verb sein is a quiet reminder that language and being are deeply intertwined.

2. In French: Sein – The Breast and Beyond

Now shift to French, and sein means something entirely different. Pronounced s (like sang without the ‘g’), it literally translates to “breast” or “bosom.” But the French language, always rich in metaphor, doesn’t stop at the literal body.

Consider the expression “au sein de” — literally “in the breast of,” but used to mean “within” or “at the heart of.”

For example:

- Au sein de l’entreprise – Within the company

- Au sein de la famille – Within the family

In this figurative sense, sein evokes closeness, nurturing, and belonging. It’s about being inside something that holds you, whether that’s a community, a home, or a movement.

The word also appears in French poetry and psychoanalytic thought. In early psychoanalysis, especially in the work of Melanie Klein, le sein (the breast) symbolized the infant’s first connection to the world—both a source of nourishment and, at times, frustration. That dual image of the “good breast” and “bad breast” shaped decades of thinking about desire and attachment.

So while in everyday speech sein may seem purely anatomical, in literature and theory it’s deeply symbolic—an emblem of life, love, and origin.

3. In Philosophy: Sein as Being Itself

In German philosophy, Sein takes on its most profound meaning. Capitalized, it no longer refers to the verb but to Being itself—the essence of existence.

This philosophical sense became central in the works of Martin Heidegger, one of the most influential (and controversial) thinkers of the 20th century. Heidegger’s masterpiece, Sein und Zeit (Being and Time), asks a deceptively simple question: What does it mean to be?

Heidegger argues that for centuries, Western philosophy has talked endlessly about “things that exist” but rarely about existence itself. He distinguishes between Sein (Being) and Seiendes (beings—the things that have being). His mission was to bring our attention back to Sein—the underlying condition that allows anything to exist at all.

This might sound abstract, but it has practical power. To think about Sein is to think about presence, awareness, and meaning. It’s about realizing that existence isn’t just something we take part in—it’s something we continuously interpret and shape.

Heidegger’s use of Sein inspired generations of philosophers, from existentialists to deconstructionists, to rethink what it means to live authentically, to act, and to “be” in a world that often feels mechanical or detached.

4. A Word That Connects Us

What makes sein fascinating is how its meanings intersect. Across languages, it points toward presence, intimacy, and existence. Whether it’s a German student saying Ich bin hier, a French poet writing about le sein maternel, or a philosopher asking what “being” even means, sein circles the same mystery: to be is to belong, to connect, to exist in relation to something else.

The word reminds us that language isn’t just a system of rules—it’s a living reflection of how humans understand life. Each version of sein—verb, noun, or concept—expresses a different aspect of being alive.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does “sein” mean in German?

In German, sein means “to be.” It’s the most essential verb, used to describe existence, identity, and state. Example: Ich bin glücklich – I am happy.

Q2: How do you conjugate “sein”?

Present: ich bin, du bist, er/sie/es ist, wir sind, ihr seid, sie sind.

Past: ich war, du warst, er war, wir waren, ihr wart, sie waren.

Q3: What does “sein” mean in French?

In French, sein means “breast” or “bosom.” It can also mean “within” when used in idioms like au sein de.

Q4: Is the French and German “sein” the same word?

No. They come from entirely different roots. The German sein is from Proto-Germanic origins meaning “to exist.” The French sein comes from Latin sinus, meaning “curve” or “bosom.”

Q5: What is “Sein” in philosophy?

In German philosophy, Sein (capitalized) refers to “Being” — the condition of existence itself. It’s central to Heidegger’s Being and Time, which explores what it truly means to exist.

Q6: Why is “sein” such an important word?

Because it captures the most fundamental idea of all — being. Every language finds a way to express it, but in sein, we see it from multiple angles: the act of living, the space of belonging, and the mystery of existence.

Final Thought:

Whether whispered in love, spoken in daily conversation, or pondered in philosophy, sein reminds us of something simple yet profound: we are, and that matters.